Before we see this work, there is a need for some technology background…

The old way

There are many Windows-based applications that are designed to use some of the numerous interfaces that are built into Windows Explorer that exist for the purpose of making it quite easy to access the app (full app, or part of it) without the user having to launch the app from the start menu. Usually these are just conveniences for things the user could do another way with more work, but sometimes it is a prime part of the application design workflow. Some examples of these explorer interfaces include:

- File Type Association – Files are displayed with the icon of the app and double click opens the app with that file.

- Shell Interface Menus – A hard-coded verb that appears in the menu when you right click on an associated file type that will start the app with the file and usually another command line parameter associated with the verb. For example, edit or print.

- Shell Extension Context Menus – This is a COM in-process dll that is triggered (activated) by explorer when you right click on certain file types. Explorer loads and then calls this handler to determine what menus to add to the menu list. This allows the dll to choose which items to put up based on the context of the situation. This could involve the name of the file, the presence (or not) of other files in the same folder, or if it is a Monday and the second letter and the second letter of the user’s name is the letter I.

- Other types of Shell Extensions – Although there is no official list, I have found that there are at least 24 different types of Shell Extensions that are implemented in Windows. They are all COM based dlls associated with a file type (or the wildcard * for any type of file) to be loaded by the explorer process for some purpose and triggered by actions associated with the extension type. Some examples:

- The Preview handler activates if the explorer View->Preview pane is activated. This allows you to see inside file contents in that Preview pane without opening the file. For example, you could browse a folder of PDF files and see the first page of each in the preview pane and you go up and down the list.

- The Property Data handler activates if the explorer View->Details pane is activated. This allows you to see inside the file contents using structured data property. So, for example, if you had a folder filled with recipe files, you could browse through the list to view what ingredients you’d have to have on hand to make something for dinner tonight. Just single click on one and then up/down arrow between files.

- The Drag and Drop handler activates when you start to drag a file, for example to show if dropping the file would result in a copy or move operation depending on where you have dragged the file to. This is based on the file type you are dragging.

- Meanwhile the Drop Target Hander activates only when you drop the file, but activation is based on the file you are dropping onto. Like if you dropped a file onto a .zip file.

All of these things have been built into Windows for a really long time, and all involve the application installer writing directly into the Windows Registry to register their handlers.

That part is often messy and causes problems on systems. There are file type conflicts as lots of apps want to work with the more common file types. And then application installers often don’t play well with others when adding themselves into the registry and are more often really lazy about cleanup when uninstalling. Microsoft tried to mitigate this in the past with things like “Registered Applications”, but this was often ignored by vendors, so it was not effective in solving the problems.

The new way

Newer install formats (AppX for UWP apps, MSIX, and even App-V) support a subset of those old capabilities, but instead of writing directly into the Windows Registry as it was done in the past, registration occurs in a different and clean way. Basically, the needs are expressed internal to the AppXManifest file, and it is up to the installer technology to decide how to make the system registration.

Now in App-V, this resulted in actually changing the same registry locations the original installer would have touched, but at least using HKCU rather than HKLM. And it kept a backup copy of what was there previously that it would restore if the app and this registration needed to be removed later.

Under AppX and MSIX, Microsoft came up with something better. The installation of these apps does add to the HKCU registry, just not in the same place. In fact, each package has its own place to avoid conflict, and the explorer code has been extended to also look in these new places. So adding and removing is really clean!

But not everything from the past is supported, especially in those Shell Extensions. Microsoft has been adding support for more and more of these extension types over time. This is a process that involves adding to the AppXManifest schemas for how to describe what the app has, adding support in the “appinstaller” to interpret it and manage the “external” version of this new registration, adding support to explorer to implement the runtime, and adding support to any tooling along the way (both dev tools and packaging tools like the Microsoft MSIX Packaging Tool).

When this work was done for App-V, the dev team chose to implement a generic solution for all types of Shell Extensions, but then supported only those that they had tested. With MSIX, Microsoft is working on adding support on a per-extension type basis. And they are doing this serially. The result is that we see them show up individually over time, and each type of shell extension has a unique set of elements in the AppXManifest. As the shell extensions are COM based, this too needed support to be added in the Manifest, AppInstaller, Runtime, and tooling. It would have been great if the initial versions of this COM support covered all the needs, but as these shell extensions have been added, the COM support also needed tweaking to cover different scenarios than were originally implemented. That’s a long-winded way of saying that it has been taking a while to get things supported!

What we now have

Although not present in the original MSIX release, Microsoft implemented the basic File Type Association Shell Interface verbs fairly early on. The Preview and Property Data handlers, along with some of the Context Menu handlers were added to the runtime in 20H1. Unfortunately, the most common context menu handlers didn’t work yet.

Microsoft has now added a more complete support for those Context Menu handlers. The runtime support is, at least currently, only available in Windows 11 builds. It isn’t clear if they will back port it, but the signs are not encouraging right now. Technically they document (see Support legacy context menus – MSIX | Microsoft Docs) that the AppInstaller and explorer runtime only works on build numbers above 10.0.20000 (which is Windows 11) but that the AppXManifest file must have a MaxTested value of at least 10.0.21300.

The Microsoft MSIX Packaging Tool version 1.2022.110, which was released this week, implements the detection of these shell extensions and adds them into the manifest file appropriately, no matter what OS version you use to recapture. But what happens if you do?

Example

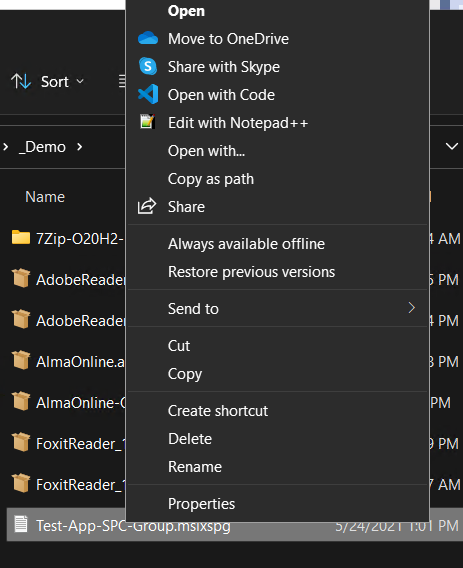

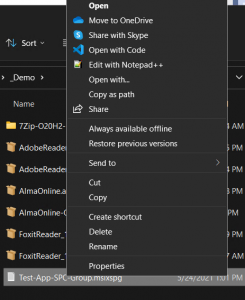

If you install the application Notepad++ onto a Windows 10 system, it includes a Shell Extension Context Menu handler that it applies to all file types on the system. Thus, if you right-click on any file in the Windows Explorer, the Context Menu handler is activated. The logic in this handler seems to be pretty basic, it adds a new menu item “Edit with Notepad++” every time (the vendor could have just used a simple Shell Integration verb for this). On the right is a screen shot from a Windows 10 system with Notepad++ natively installed and the handler activated.

it includes a Shell Extension Context Menu handler that it applies to all file types on the system. Thus, if you right-click on any file in the Windows Explorer, the Context Menu handler is activated. The logic in this handler seems to be pretty basic, it adds a new menu item “Edit with Notepad++” every time (the vendor could have just used a simple Shell Integration verb for this). On the right is a screen shot from a Windows 10 system with Notepad++ natively installed and the handler activated.

I recaptured the Notepad++ app which has one of these on a Windows 10 21H2 operating system using MMPT 1.2022.110. Although I would normally add the Package Support Framework FileRedirectionFixup to prevent the vendor auto-updater from running if I were creating the package for production use, I ignored that for this simple test and packaged without the PSF.

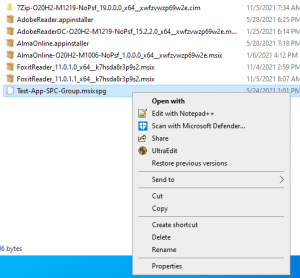

When the package is added to a Windows 10 21H2 system, the new extensions within the manifest are silently ignored, and we get what we have been seeing for a while, which is that the shell extension isn’t actually activated, and the explorer process doesn’t show the added extra menu item. This is shown in the screenshot on the right.

When the package is added to a Windows 10 21H2 system, the new extensions within the manifest are silently ignored, and we get what we have been seeing for a while, which is that the shell extension isn’t actually activated, and the explorer process doesn’t show the added extra menu item. This is shown in the screenshot on the right.

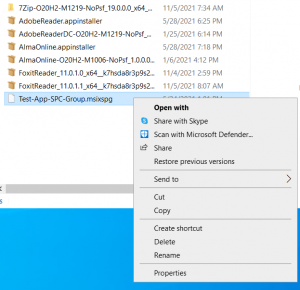

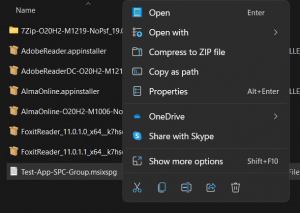

When this same package is installed onto a Windows 11 (21H2) system, the handler is registered and activated. However, Windows 11 implements the right-click popup menus different than Windows 10 did. This is true whether you natively installed the app natively or used the MSIX package. The result is that you must use a two-step process to see the added menu item. In the images below, a right click on the file produces the image on the left, after which if you select the Show more options entry you get the image on the right which contains the added extra menu item.

So with this, we finally get the Context Menus with MSIX on Windows 11. But to be honest, since they are only available on Windows 11 and Windows 11 adds an extra mouse click to get the new menu, it isn’t all that useful. Even the added Shell Integration Verbs only show up on that extra page. The extra click needed is pretty effective is getting me to not want to use these shell integrations and context menus and just go back to launching the app I know I want and finding the file.